new bike part 3: playing with BikeCad

BikeCad is cool. It lets you play around with bike designs and geometries. Bike geometries are generally over-constrained: each dimension depends on other dimensions, so specifying a set of random numbers will not result in a build-able bike. BikeCad takes care of the constraints, doing the trigonometric operations necessary to convert between angles and distances and postions in space.

My idea: a randonneuring bike with modern components and a position similar to my Ritchey Breakaway: comfortable but still race-worthy. When I think of randonneuring bikes I think of a bike built to handle anything: rain, rough roads, dirt, pavement, long distances, climbing, descending, carrying supplies, and most importantly speed. Just because I want these other things doesn't mean I don't want a bike which doesn't handle well on descents, doesn't feel responsive on climbs, and won't allow me to pull through on pacelines without eating a wall of wind.

I've described my BikeCad fun before, but it's worth a reprise.

In the past, randonneuring bikes to me conjured images of Grant Peterson or Pineapple Bob riding in floppy clothing, downtube shifters, slow heavy tires, handlebars rising to the top of the saddle, and a monster dose of attitude. Not for me.

But then I started reading Jan Heine, attracted not by the bikes he promotes, but rather by his experimental focus. Bicycle Quarterly is an exceptional magazine. You don't need to agree with his conclusions in all cases. It's his attempt toward objectivity which is refreshing. From reading the magazine, both new issues and back issues, I developed an appreciation for the history of randonneuring, particularly in France, where it espoused a culture of friendly competition, similar to what I promote in my work with the Low-Key Hillclimbs.

But just because randonneuring in France was at its height in the 1940's and 1950's doesn't mean bike design needs to be frozen in time from that era. The concept and philosophy which drove the bike designs from that era remain valid, but the details need not always be the same. The aesthetic baggage that implied it needed to be has held back the popularity of the engineering advantages.

The key issue is bike design has been driven by racing, even for bikes (most of them) which will never race. Road bikes, mountain bikes, cyclocross, track bikes, even "gravel grinders" are designed to be the fastest over a certain terrain with certain rules. But we don't drive cars designed for racing, why should our bikes be? There's realities associated with more typical riding which compels more substantial deviations from the standards of competition.

Some of these include fenders for when it rains, fat tires for rough roads, a bell to warn pedestrians and slower cyclists you're approaching, and the need to carry stuff.

On the rough road front: I don't buy the usual "roads have gotten better since the 1940's" line you see too often: there's plenty of rough roads in the San Francisco Bay area, and if you avoid them because your tires can't handle it, that's your loss. The recent popularity increase of cyclocross and more recently gravel grinder bikes has proven that life's not all pristine asphalt.

On carrying capacity: the paradigm that if you need something you finish your bike ride, get into your car, then drive back to get it is absurd. Yesterday I was on a ride and passed a farmer's market. Yet all I had room for in my pockets was a small bag of dried parsimmons. They were delicious. I would have liked to purchase more. I would have liked to add some of the other dried fruit available. Yet I had no storage capacity on my bike.

When I ride to work, a 72 km trip from San Francisco to Mountain View, I take my backpack, even if it's just for a change of clothes. So much for "optimized for speed": a back-pack is terrible aerodynamics (well, not always). A backpack isn't super-terrible: I did a 100-mile commute with one. But clearly it's generally more desirable to carry weight on bike.

So I played around on BikeCad. Here was the result (image linked to BikeCad page):

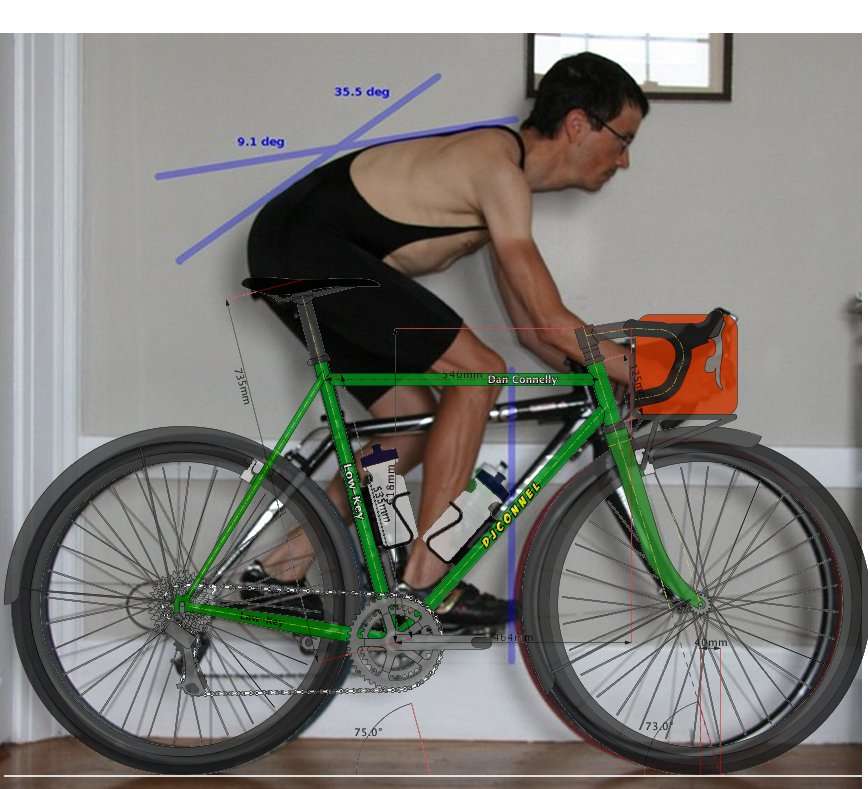

The geometry was a bit of a guess. But I could check it against my position on my race bike:

The bars are slightly shifted to allow for a more comfortable cruising position, or for a more comfortable position when climbing dirt trails, but otherwise it's fairly similar.

I'm not a professional bike designer, though, so I wanted someone who knew what they were doing, or at least was free from my personal biases, take a look. In particular, my initial design (from that older blog post) was for 650B tires. Yet I was talked into "700C" wheels because of the more widespread availability of tires and wheels, as well as compatibility with my existing wheel stock. The images I showed here are with that revision.

Comments